Who Pays Tariffs And Where Does That Money Go To

A tariff is a taxation imposed by the regime of a state or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the authorities, import duties can too exist a form of regulation of strange trade and policy that taxes foreign products to encourage or safeguard domestic industry. Tariffs are amongst the most widely used instruments of protectionism, along with import and export quotas.

Tariffs can be stock-still (a abiding sum per unit of imported appurtenances or a percent of the price) or variable (the corporeality varies according to the cost). Taxing imports means people are less likely to buy them every bit they become more expensive. The intention is that they buy local products instead, boosting their land's economy. Tariffs therefore provide an incentive to develop production and replace imports with domestic products. Tariffs are meant to reduce force per unit area from foreign competition and reduce the trade deficit. They take historically been justified every bit a means to protect infant industries and to let import commutation industrialization. Tariffs may also be used to rectify artificially low prices for certain imported goods, due to 'dumping', consign subsidies or currency manipulation.

There is near unanimous consensus among economists that tariffs take a negative outcome on economical growth and economical welfare, while free trade and the reduction of trade barriers has a positive effect on economic growth.[1] [2] [3] [iv] [5] [6] [seven] Although trade liberalization tin can sometimes consequence in large and unequally distributed losses and gains, and tin can, in the short run, cause significant economic dislocation of workers in import-competing sectors,[8] free merchandise has advantages of lowering costs of goods and services for both producers and consumers.[9]

Etymology [edit]

The English term tariff derives from the French: tarif, lit.'set cost' which is itself a descendant of the Italian: tariffa, lit.'mandated price; schedule of taxes and customs' which derives from Medieval Latin: tariffe, lit.'ready cost'. This term was introduced to the Latin-speaking earth through contact with the Turks and derives from the Ottoman Turkish: تعرفه, romanized: taʿrife , lit.'listing of prices; table of the rates of community'. This Turkish term is a loanword of the Persian: تعرفه, romanized: taʿrefe , lit.'set cost, receipt'. The Persian term derives from Standard arabic: تعريف, romanized: taʿrīf , lit.'notification; description; definition; proclamation; exclamation; inventory of fees to exist paid' which is the verbal noun of Arabic: عرف, romanized: ʿarafa , lit.'to know; to can; to recognise; to notice out'.[10] [11] [12] [13] [fourteen] [15]

History [edit]

Average tariff rates for selected countries (1913–2007)

Tariff rates in Japan (1870–1960)

Average tariff rates in Spain and Italy (1860–1910)

Average levels of duties, 1875 and 1913[16]

Aboriginal Hellenic republic [edit]

In the urban center country of Athens, the port of Piraeus enforced a system of levies to raise taxes for the Athenian government. Grain was a key commodity that was imported through the port, and Piraeus was one of the main ports in the due east Mediterranean. A levy of 2 per centum was placed on goods arriving in the market through the docks of Piraeus. Despite the Peloponnesian War preceding yr 399 BC[ vague ], Piraeus had documented a revenue enhancement income of 1,800 in harbor ante.[17] The Athenian government likewise placed restrictions on the lending of money and transport of grain to only exist allowed through the port of Piraeus.[18]

Peachy United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland [edit]

In the 14th century, Edward 3 (1312–1377) took interventionist measures, such every bit banning the import of woollen cloth in an try to develop local woollen cloth manufacturing. Starting time in 1489, Henry VII took actions such as increasing consign duties on raw wool. The Tudor monarchs, specially Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, used protectionism, subsidies, distribution of monopoly rights, government-sponsored industrial espionage and other means of government intervention to develop the wool manufacture, leading to England became the largest wool-producing nation in the world.[19]

A protectionist turning point in British economic policy came in 1721, when policies to promote manufacturing industries were introduced past Robert Walpole. These included increased tariffs on imported foreign manufactured appurtenances, and export subsidies. These policies were similar to those used past countries such as Nihon, Korea and Taiwan after the Second World War. In add-on, in its colonies, Bang-up United kingdom imposed a ban on advanced manufacturing activities that information technology did not desire to see developed. Britain besides banned exports from its colonies that competed with its ain products at home and away, forcing the colonies to leave the about profitable industries in Britain's hands.[xix]

In 1800, Britain, with about 10% of Europe'south population, supplied 29% of all grunter iron produced in Europe, a proportion that had risen to 45% past 1830. Per capita industrial production was fifty-fifty higher: in 1830 it was 250% higher than in the rest of Europe, upwardly from 110% in 1800.[ need quotation to verify ]

Protectionist policies of industrial promotion continued until the mid-19th century. At the showtime of that century, the average tariff on British manufactured goods was about l%, the highest of all major European countries. Thus, according to economic historian Paul Bairoch, Britain's technological accelerate was accomplished "backside loftier and enduring tariff barriers". In 1846, the land's per capita rate of industrialization was more than than twice that of its closest competitors.[19] Even afterwards adopting free merchandise for about goods, Britain continued to closely regulate trade in strategic upper-case letter goods, such equally machinery for the mass production of textiles.

Free trade in U.k. began in hostage with the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, which was equivalent to free trade in grain. The Corn Acts had been passed in 1815 to restrict wheat imports and to guarantee the incomes of British farmers; their repeal devastated Uk'southward erstwhile rural economic system, just began to mitigate the effects of the Bully Dearth in Ireland. Tariffs on many manufactured appurtenances were also abolished. Simply while liberalism was progressing in Britain, protectionism connected on the European mainland and in the United states.[19]

On June 15, 1903, the Secretary of Land for Foreign Affairs, Henry Little-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, fabricated a oral communication in the Business firm of Lords in which he dedicated fiscal retaliation against countries that practical loftier tariffs and whose governments subsidized products sold in U.k. (known equally "premium products", after called "dumping"). The retaliation was to take the form of threats to impose duties in response to goods from that country. Liberal unionists had split from the liberals, who advocated free trade, and this speech marked a turning point in the grouping's slide toward protectionism. Landsdowne argued that the threat of retaliatory tariffs was similar to gaining respect in a room of gunmen past pointing a big gun (his exact words were "a gun a piffling bigger than everyone else'south"). The "Big Revolver" became a slogan of the time, often used in speeches and cartoons.[20]

In response to the Dandy Depression, Britain finally abandoned costless trade in 1932 and reintroduced tariffs on a large scale, noticing that information technology had lost its production chapters to protectionist countries like the United States and Weimar Frg.[19]

United states of america [edit]

Average tariff rates (France, UK, US)

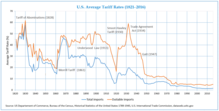

Boilerplate tariff rates in Usa (1821–2016)

US Trade Balance and Trade Policy (1895–2015)

Before the new Constitution took effect in 1788, the Congress could non levy taxes—it sold state or begged money from the states. The new national government needed revenue and decided to depend upon a taxation on imports with the Tariff of 1789.[21] The policy of the U.S. before 1860 was low tariffs "for acquirement only" (since duties continued to fund the national authorities).[22] A high tariff was attempted in 1828 just the S denounced it equally a "Tariff of Abominations" and it almost caused a rebellion in South Carolina until it was lowered.[23]

Betwixt 1816 and the end of the 2d World War, the United States had one of the highest average tariff rates on manufactured imports in the world. According to Paul Bairoch, the United States was "the homeland and breastwork of modern protectionism"during this period [24]

Many American intellectuals and politicians during the country's catching-upward period felt that the gratis trade theory advocated past British classical economists was not suited to their country. They argued that the country should develop manufacturing industries and utilize government protection and subsidies for this purpose, as Uk had washed earlier them. Many of the great American economists of the time, until the last quarter of the 19th century, were stiff advocates of industrial protection: Daniel Raymond who influenced Friedrich List, Mathew Carey and his son Henry, who was one of Lincoln's economic advisers. The intellectual leader of this movement was Alexander Hamilton, the outset Secretary of the Treasury of the United States (1789-1795). Thus, it was against David Ricardo'south theory of comparative advantage that the United states protected its industry. They pursued a protectionist policy from the commencement of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century, after the Second World War.[24] [25]

In Written report on Articles, considered the beginning text to express modernistic protectionist theory, Alexander Hamilton argued that if a land wished to develop a new activity on its soil, it would have to temporarily protect information technology. According to him, this protection confronting foreign producers could take the form of import duties or, in rare cases, prohibition of imports. He called for community barriers to allow American industrial development and to help protect infant industries, including bounties (subsidies) derived in role from those tariffs. He too believed that duties on raw materials should exist mostly depression.[26] Hamilton argued that despite an initial "increment of price" caused past regulations that command foreign competition, once a "domestic industry has attained to perfection… it invariably becomes cheaper.[27] He believed that political independence was predicated upon economic independence. Increasing the domestic supply of manufactured goods, particularly state of war materials, was seen as an outcome of national security. And he feared that Britain's policy towards the colonies would condemn the United States to be only producers of agronomical products and raw materials.[24] [27]

Britain initially did not want to industrialize the American colonies, and implemented policies to that effect (for example, banning high value-added manufacturing activities). Under British rule, America was denied the utilize of tariffs to protect its new industries. This explains why, afterward independence, the Tariff Act of 1789 was the second nib of the Republic signed by President Washington allowing Congress to impose a fixed tariff of 5% on all imports, with a few exceptions.[27]

The Congress passed a tariff act (1789), imposing a 5% apartment charge per unit tariff on all imports.[28] Between 1792 and the war with Britain in 1812, the average tariff level remained around 12.5%. In 1812 all tariffs were doubled to an boilerplate of 25% in order to cope with the increase in public expenditure due to the war. A significant shift in policy occurred in 1816, when a new law was introduced to go along the tariff level close to the wartime level—especially protected were cotton fiber, woolen, and atomic number 26 appurtenances.[29] The American industrial interests that had blossomed considering of the tariff lobbied to go on it, and had it raised to 35 percent in 1816. The public approved, and by 1820, America's average tariff was up to xl percent.

In the 19th century, statesmen such as Senator Henry Clay connected Hamilton's themes within the Whig Party under the proper noun "American System which consisted of protecting industries and developing infrastructure in explicit opposition to the "British system" of gratis trade.[30] [ full citation needed ] Before 1860 they were always defeated by the low-tariff Democrats.[31]

From 1846 to 1861, during which American tariffs were lowered but this was followed by a serial of recessions and the 1857 panic, which somewhen led to higher demands for tariffs than President James Buchanan, signed in 1861 (Morrill Tariff).

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), agrarian interests in the South were opposed to whatever protection, while manufacturing interests in the N wanted to maintain it. The war marked the triumph of the protectionists of the industrial states of the Due north over the free traders of the South. Abraham Lincoln was a protectionist like Henry Clay of the Whig Political party, who advocated the "American system" based on infrastructure development and protectionism. In 1847, he declared: "Give usa a protective tariff, and we volition have the greatest nation on earth". Once elected, Lincoln raised industrial tariffs and after the state of war, tariffs remained at or above wartime levels. High tariffs were a policy designed to encourage rapid industrialisation and protect the high American wage rates.[27]

The policy from 1860 to 1933 was usually high protective tariffs (apart from 1913 to 1921). Afterward 1890, the tariff on wool did affect an important industry, but otherwise the tariffs were designed to keep American wages loftier. The conservative Republican tradition, typified by William McKinley was a loftier tariff, while the Democrats typically called for a lower tariff to help consumers but they e'er failed until 1913.[32] [33]

In the early 1860s, Europe and the The states pursued completely different merchandise policies. The 1860s were a menses of growing protectionism in the United States, while the European free trade stage lasted from 1860 to 1892. The tariff average rate on imports of manufactured goods was in 1875 from 40% to 50% in the Us against 9% to 12% in continental Europe at the height of free trade.

In 1896, the GOP pledged platform pledged to "renew and emphasize our allegiance to the policy of protection, as the barrier of American industrial independence, and the foundation of evolution and prosperity. This true American policy taxes strange products and encourages domicile industry. Information technology puts the burden of revenue on strange goods; information technology secures the American market place for the American producer. It upholds the American standard of wages for the American workingman".[34]

In 1913, following the electoral victory of the Democrats in 1912, there was a pregnant reduction in the boilerplate tariff on manufactured appurtenances from 44% to 25%. Notwithstanding, the First Earth State of war rendered this bill ineffective, and new "emergency" tariff legislation was introduced in 1922, after the Republicans returned to power in 1921.[27]

According to economic historian Douglas Irwin, a common myth well-nigh United states of america trade policy is that low tariffs harmed American manufacturers in the early 19th century and then that high tariffs fabricated the United states of america into a neat industrial power in the late 19th century.[35] A review by the Economist of Irwin's 2017 book Ambivalent over Commerce: A History of US Merchandise Policy notes:[35]

Political dynamics would pb people to see a link between tariffs and the economic bicycle that was not there. A boom would generate plenty revenue for tariffs to autumn, and when the bust came force per unit area would build to enhance them once again. By the time that happened, the economy would be recovering, giving the impression that tariff cuts acquired the crash and the opposite generated the recovery. Mr Irwin also methodically debunks the thought that protectionism fabricated America a great industrial power, a notion believed by some to offer lessons for developing countries today. Every bit its share of global manufacturing powered from 23% in 1870 to 36% in 1913, the admittedly high tariffs of the time came with a price, estimated at effectually 0.5% of Gdp in the mid-1870s. In some industries, they might have sped up development by a few years. Only American growth during its protectionist menstruation was more than to do with its abundant resources and openness to people and ideas.

The economist Ha-Joon Chang disagrees with the idea that the United States has developed and reached the tiptop of the world economic hierarchy by adopting complimentary trade. On the opposite, according to him, they have adopted an interventionist policy to promote and protect their industries through tariffs. It was their protectionist policy that would accept immune the U.s.a. to experience the fastest economic growth in the world throughout the 19th century and into the 1920s.[19]

Tariffs and the Keen Low [edit]

Most economists concord the opinion that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Human action in the United States did not greatly worsen the Great Depression:

Milton Friedman held the opinion that the tariffs of 1930 did not cause the Great Depression, instead he blamed the lack of sufficient action on the part of the Federal Reserve. Douglas A. Irwin wrote: "near economists, both liberal and conservative, doubtfulness that Smoot–Hawley played much of a role in the subsequent contraction".[36]

Peter Temin, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Applied science, explained that a tariff is an expansionary policy, similar a devaluation as it diverts demand from foreign to dwelling house producers. He noted that exports were 7 percent of GNP in 1929, they fell past 1.v percent of 1929 GNP in the adjacent two years and the fall was offset past the increase in domestic demand from tariff. He concluded that contrary the popular statement, contractionary effect of the tariff was small.[37]

William Bernstein wrote: "Betwixt 1929 and 1932, real GDP fell 17 per centum worldwide, and by 26 percent in the United States, simply most economical historians now believe that but a minuscule part of that huge loss of both world Gross domestic product and the The states' Gross domestic product can exist ascribed to the tariff wars. .. At the time of Smoot-Hawley's passage, trade volume accounted for simply about 9 percent of world economic output. Had all international merchandise been eliminated, and had no domestic apply for the previously exported goods been found, earth Gdp would take fallen past the same amount — 9 percent. Betwixt 1930 and 1933, worldwide trade volume cruel off by one-3rd to one-half. Depending on how the falloff is measured, this computes to 3 to five percent of globe GDP, and these losses were partially made up by more expensive domestic goods. Thus, the damage done could not perchance have exceeded i or 2 per centum of earth Gross domestic product — nowhere almost the 17 percent falloff seen during the Great Depression... The inescapable conclusion: reverse to public perception, Smoot-Hawley did not cause, or even significantly deepen, the Smashing Depression,"(A Splendid Exchange: How Merchandise Shaped the Globe, William Bernstein)[ commendation needed ]

Nobel laureate Maurice Allais argued: 'Starting time, virtually of the trade wrinkle occurred between Jan 1930 and July 1932, before most protectionist measures were introduced, except for the limited measures applied by the U.s. in the summertime of 1930. It was therefore the collapse of international liquidity that caused the contraction of trade[8], not customs tariffs'.[ citation needed ]

Russia [edit]

The Russian Federation adopted more protectionist merchandise measures in 2013 than whatever other country, making it the globe leader in protectionism. It alone introduced 20% of protectionist measures worldwide and one-third of measures in the G20 countries. Russia'due south protectionist policies include tariff measures, import restrictions, sanitary measures, and straight subsidies to local companies. For example, the government supported several economical sectors such as agriculture, space, automotive, electronics, chemistry, and energy.[38] [39]

Bharat [edit]

From 2017, every bit function of the promotion of its "Brand in Bharat" programme[xl] to stimulate and protect domestic manufacturing industry and to gainsay current account deficits, India has introduced tariffs on several electronic products and "non-essential items". This concerns items imported from countries such as People's republic of china and S Korea. For instance, Republic of india'south national solar free energy programme favours domestic producers by requiring the use of Indian-fabricated solar cells.[41] [42] [43]

Armenia [edit]

Armenia, a state located in Western Asia, established its custom service in 1992 after the dissolution of the Soviet Wedlock. When Armenia became a fellow member of the EAEU, it was given access to the Eurasian Customs Union in 2015; this resulted in by and large tariff-free merchandise with other members and an increased number of import tariffs from exterior of the community union. Armenia does not currently accept export taxes. In addition, it does not declare temporary imports duties and credit on authorities imports or pursuant to other international assistance imports. [44]

Customs duty [edit]

A community duty or due is the indirect tax levied on the import or export of appurtenances in international trade. In economics a duty is also a kind of consumption taxation. A duty levied on goods beingness imported is referred to as an 'import duty', and one levied on exports an 'export duty'.

Adding of community duty [edit]

Customs duty is calculated on the determination of the 'assess-able value' in case of those items for which the duty is levied advertizement valorem . This is often the transaction value unless a customs officeholder determines appraise-able value in accordance with the Harmonized System. For certain items like petroleum and alcohol, customs duty is realized at a specific charge per unit applied to the volume of the import or export consignments.[ citation needed ]

Harmonized System of Classification [edit]

For the purpose of assessment of customs duty, products are given an identification code that has come to be known equally the Harmonized System code. This lawmaking was developed past the World Customs Organization based in Brussels. A 'Harmonized Organisation' code may be from 4 to 10 digits. For example, 17.03 is the HS code for molasses from the extraction or refining of saccharide. Still, within 17.03, the number 17.03.xc stands for "Molasses (Excluding Pikestaff Molasses)".

Introduction of Harmonized System codes in the 1990s has largely replaced the previous Standard International Trade Nomenclature (SITC), though SITC remains in utilize for statistical purposes.[ citation needed ] In drawing upwards the national tariff, the revenue departments often specifies the rate of customs duty with reference to the HS code of the product. In some countries and customs unions, half-dozen-digit HS codes are locally extended to 8 digits or x digits for further tariff bigotry: for example the European Matrimony uses its 8-digit CN (Combined Nomenclature) and 10-digit TARIC codes.[ citation needed ]

[edit]

The national customs authority in each state is responsible for collecting taxes on the import into or export of goods out of the country. Normally the community authority, operating under national law, is authorized to examine cargo in order to ascertain actual description, specification volume or quantity, so that the assessable value and the rate of duty may be correctly determined and applied.[ commendation needed ]

Evasion [edit]

Evasion of community duties takes place mainly in two ways. In ane, the trader under-declares the value so that the assessable value is lower than actual. In a similar vein, a trader can evade community duty by understatement of quantity or book of the production of merchandise. A trader may also evade duty by misrepresenting traded goods, categorizing appurtenances as items which concenter lower customs duties. The evasion of customs duty may take place with or without the collaboration of customs officials. Evasion of customs duty does not necessarily constitute smuggling. [ citation needed ]

Duty-gratis goods [edit]

Many countries permit a traveller to bring appurtenances into the country duty-costless. These goods may exist bought at ports and airports or sometimes within one land without attracting the usual government taxes and and then brought into another land duty-free. Some countries specify 'duty-free allowances' which limit the number or value of duty-gratis items that i person can bring into the country. These restrictions often apply to tobacco, wine, spirits, cosmetics, gifts and souvenirs. Often foreign diplomats and United nations officials are entitled to duty-free goods.[ citation needed ]

Deferment of tariffs and duties [edit]

Goods may be imported and stocked duty-free in a bonded warehouse: duty becomes payable on leaving the facility.[ commendation needed ] Products may sometimes be imported into a gratis economical zone (or 'gratuitous port'), processed at that place, then re-exported without being subject to tariffs or duties. Co-ordinate to the 1999 Revised Kyoto Convention, a "'free zone' means a office of the territory of a contracting party where any goods introduced are by and large regarded, insofar as import duties and taxes are concerned, equally being outside the community territory".[45]

Economic assay [edit]

Effects of import tariff, which hurts domestic consumers more than domestic producers are helped. Higher prices and lower quantities reduce consumer surplus by areas A+B+C+D, while expanding producer surplus past A and regime revenue by C. Areas B and D are dead-weight losses, surplus lost by consumers and overall.[46] For a more detailed assay of this diagram, run across Free merchandise#Economics

Neoclassical economic theorists tend to view tariffs as distortions to the costless market. Typical analyses find that tariffs tend to do good domestic producers and regime at the expense of consumers, and that the net welfare effects of a tariff on the importing country are negative due to domestic firms not producing more efficiently since in that location is a lack of external competition.[47] Therefore, domestic consumers are affected since the price is higher due to high costs acquired due to inefficient production[47] or if firms aren't able to source cheaper material externally thus reducing the affordability of the products. Normative judgments often follow from these findings, namely that it may be disadvantageous for a country to artificially shield an industry from world markets and that information technology might exist meliorate to let a collapse to have place. Opposition to all tariff aims to reduce tariffs and to avoid countries discriminating between differing countries when applying tariffs. The diagrams at right prove the costs and benefits of imposing a tariff on a good in the domestic economy.[46]

Imposing an import tariff has the post-obit effects, shown in the first diagram in a hypothetical domestic market for televisions:

- Price rises from globe cost Pow to higher tariff cost Pt.

- Quantity demanded by domestic consumers falls from C1 to C2, a movement along the demand bend due to higher toll.

- Domestic suppliers are willing to supply Q2 rather than Q1, a motion along the supply curve due to the college price, so the quantity imported falls from C1-Q1 to C2-Q2.

- Consumer surplus (the area under the demand curve but to a higher place price) shrinks by areas A+B+C+D, as domestic consumers face higher prices and consume lower quantities.

- Producer surplus (the area in a higher place the supply curve but below price) increases past area A, as domestic producers shielded from international competition can sell more of their product at a higher price.

- Government tax revenue is the import quantity (C2-Q2) times the tariff toll (Pw - Pt), shown as area C.

- Areas B and D are deadweight losses, surplus formerly captured past consumers that at present is lost to all parties.

The overall alter in welfare = Change in Consumer Surplus + Modify in Producer Surplus + Modify in Authorities Revenue = (-A-B-C-D) + A + C = -B-D. The final state after imposition of the tariff is indicated in the 2nd diagram, with overall welfare reduced by the areas labeled "societal losses", which correspond to areas B and D in the get-go diagram. The losses to domestic consumers are greater than the combined benefits to domestic producers and authorities.[46]

That tariffs overall reduce welfare is non a controversial topic among economists. For example, the Academy of Chicago surveyed almost 40 leading economists in March 2018 asking whether "Imposing new U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum will improve Americans' welfare." About two-thirds strongly disagreed with the argument, while one 3rd disagreed. None agreed or strongly agreed. Several commented that such tariffs would assist a few Americans at the expense of many.[48] This is consistent with the explanation provided above, which is that losses to domestic consumers outweigh gains to domestic producers and government, past the amount of deadweight losses.[49]

Tariffs are more inefficient than consumption taxes.[l]

A 2021 written report plant that across 151 countries over the period 1963–2014, "tariff increases are associated with persistent, economically and statistically significant declines in domestic output and productivity, as well as higher unemployment and inequality, real exchange charge per unit appreciation, and insignificant changes to the trade residual."[51]

Optimal tariff [edit]

For economic efficiency, free trade is often the all-time policy, however levying a tariff is sometimes second best.

A tariff is called an optimal tariff if information technology is ready to maximize the welfare of the country imposing the tariff.[52] It is a tariff derived past the intersection between the trade indifference curve of that country and the offer curve of some other country. In this case, the welfare of the other land grows worse simultaneously, thus the policy is a kind of beggar thy neighbor policy. If the offer bend of the other country is a line through the origin betoken, the original country is in the condition of a small country, so any tariff worsens the welfare of the original country.[53] [54]

It is possible to levy a tariff as a political policy selection, and to consider a theoretical optimum tariff rate.[55] However, imposing an optimal tariff will oft lead to the foreign land increasing their tariffs as well, leading to a loss of welfare in both countries. When countries impose tariffs on each other, they will attain a position off the contract bend, significant that both countries' welfare could exist increased by reducing tariffs.[56]

Political assay [edit]

The tariff has been used as a political tool to plant an independent nation; for example, the U.s.a. Tariff Act of 1789, signed specifically on July 4, was called the "2nd Annunciation of Independence" by newspapers considering information technology was intended to be the economic means to achieve the political goal of a sovereign and contained Us.[57]

The political impact of tariffs is judged depending on the political perspective; for case the 2002 United States steel tariff imposed a xxx% tariff on a diversity of imported steel products for a menstruum of three years and American steel producers supported the tariff.[58]

Tariffs can emerge as a political issue prior to an election. In the leadup to the 2007 Australian Federal election, the Australian Labor Party announced it would undertake a review of Australian machine tariffs if elected.[59] The Liberal Party made a similar commitment, while independent candidate Nick Xenophon announced his intention to innovate tariff-based legislation as "a matter of urgency".[60]

Unpopular tariffs are known to take ignited social unrest, for example the 1905 meat riots in Chile that adult in protest against tariffs applied to the cattle imports from Argentine republic.[61] [62]

Arguments in favor of tariffs [edit]

Protection of baby industry [edit]

Postulated in the United States by Alexander Hamilton at the terminate of the 18th century, by Friedrich List in his 1841 book Das nationale Arrangement der politischen Oekonomie and past John Stuart Manufacturing plant, the argument made in favour of this category of tariffs was this: should a land wish to develop a new economical activity on its soil, it would accept to temporarily protect it. In their view, it is legitimate to protect certain activities by customs barriers in order to give them time to grow, to reach a sufficient size and to benefit from economies of scale through increased production and productivity gains. This would allow them to become competitive in order to face up international competition. Indeed, a company needs to reach a certain production book to be profitable in order to recoup for its fixed costs. Without protectionism, foreign products – which are already profitable because of the volume of production already carried out on their soil – would arrive in the country in large quantities at a lower price than local production. The recipient country's nascent industry would quickly disappear. A firm already established in an manufacture is more efficient because it is more adjusted and has greater product capacity. New firms therefore suffer losses due to a lack of competitiveness linked to their 'apprenticeship' or catch-up menstruation. Past being protected from this external competition, firms can therefore establish themselves on their domestic market. As a result, they benefit from greater freedom of manoeuvre and greater certainty regarding their profitability and future development. The protectionist phase is therefore a learning period that would permit the to the lowest degree developed countries to learn general and technical know-how in the fields of industrial product in order to become competitive on international market.[63]

Co-ordinate to the economists in favour of protecting industries, free trade would condemn developing countries to being nothing more than exporters of raw materials and importers of manufactured goods. The application of the theory of comparative advantage would atomic number 82 them to specialize in the product of raw materials and extractive products and foreclose them from acquiring an industrial base. Protection of baby industries (e.g. through tariffs on imported products) would therefore be essential for developing countries to industrialize and escape their dependence on the production of raw materials.[xix]

Economist Ha-Joon Chang argues that nigh of today's adult countries accept adult through policies that are the contrary of free merchandise and laissez-faire. According to him, when they were developing countries themselves, almost all of them actively used interventionist merchandise and industrial policies to promote and protect infant industries. Instead, they would have encouraged their domestic industries through tariffs, subsidies and other measures. In his view, Britain and the United States have not reached the top of the global economical bureaucracy past adopting free trade. In fact, these two countries would accept been among the greatest users of protectionist measures, including tariffs. Equally for the East Asian countries, he points out that the longest periods of rapid growth in these countries do not coincide with extended phases of gratuitous trade, but rather with phases of industrial protection and promotion. Interventionist trade and industrial policies would have played a crucial role in their economic success. These policies would have been like to those used by Britain in the 18th century and the United States in the 19th century. He considers that infant industry protection policy has generated much ameliorate growth functioning in the developing world than free trade policies since the 1980s.[19]

In the 2d half of the 20th century, Nicholas Kaldor takes up similar arguments to allow the conversion of ageing industries.[64] In this instance, the aim was to relieve an activity threatened with extinction by external competition and to safeguard jobs. Protectionism must enable ageing companies to regain their competitiveness in the medium term and, for activities that are due to disappear, it allows the conversion of these activities and jobs.

Protection against dumping [edit]

States resorting to protectionism invoke unfair competition or dumping practices:

- Monetary manipulation: a currency undergoes a devaluation when monetary authorities decide to intervene in the strange substitution market place to lower the value of the currency against other currencies. This makes local products more competitive and imported products more than expensive (Marshall Lerner Condition), increasing exports and decreasing imports, and thus improving the trade balance. Countries with a weak currency cause trade imbalances: they take large external surpluses while their competitors have large deficits.

- Tax dumping: some tax haven states have lower corporate and personal revenue enhancement rates.

- Social dumping: when a land reduces social contributions or maintains very depression social standards (for case, in China, labour regulations are less restrictive for employers than elsewhere).

- Environmental dumping: when environmental regulations are less stringent than elsewhere.

Free trade and poverty [edit]

Sub-Saharan African countries take a lower income per capita in 2003 than twoscore years earlier (Ndulu, World Banking company, 2007, p. 33).[65] Per capita income increased by 37% between 1960 and 1980 and fell by 9% between 1980 and 2000. Africa'southward manufacturing sector'south share of GDP decreased from 12% in 1980 to 11% in 2013. In the 1970s, Africa accounted for more than than 3% of world manufacturing output, and at present accounts for 1.5%. In an Op ed article for The Guardian (Uk), Ha-Joon Chang argues that these downturns are the result of costless merchandise policies,[66] [67] and elsewhere attributes successes in some African countries such as Ethiopia and Rwanda to their abandonment of gratis trade and adoption of a "developmental state model".[67]

The poor countries that take succeeded in achieving strong and sustainable growth are those that have go mercantilists, not free traders: Prc, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan.[68] [69] [70] Thus, whereas in the 1990s, China and India had the same GDP per capita, China followed a much more mercantilist policy and now has a GDP per capita three times higher than India's.[71] Indeed, a significant part of Cathay's rise on the international trade scene does non come from the supposed benefits of international competition but from the relocations adept by companies from developed countries. Dani Rodrik points out that information technology is the countries that have systematically violated the rules of globalisation that have experienced the strongest growth.[72]

The 'dumping' policies of some countries accept too largely affected developing countries. Studies on the furnishings of gratuitous trade show that the gains induced past WTO rules for developing countries are very small.[73] This has reduced the proceeds for these countries from an estimated $539 billion in the 2003 LINKAGE model to $22 billion in the 2005 GTAP model. The 2005 LINKAGE version likewise reduced gains to 90 billion.[73] Every bit for the "Doha Round", it would take brought in only $iv billion to developing countries (including Cathay...) according to the GTAP model.[73] Still, it has been argued that the models used are actually designed to maximize the positive furnishings of trade liberalization, that they are characterized by the absence of taking into account the loss of income acquired past the finish of tariff barriers.[74]

John Maynard Keynes, tariffs and trade deficit [edit]

The turning betoken of the Dandy Depression [edit]

At the beginning of his career, Keynes was an economist close to Alfred Marshall, deeply convinced of the benefits of free trade. From the crisis of 1929 onwards, noting the commitment of the British authorities to defend the gold parity of the pound sterling and the rigidity of nominal wages, he gradually adhered to protectionist measures.[75]

On 5 Nov 1929, when heard by the Macmillan Committee to bring the British economy out of the crunch, Keynes indicated that the introduction of tariffs on imports would help to rebalance the merchandise balance. The committee'south report states in a section entitled "import control and export aid", that in an economy where there is non full employment, the introduction of tariffs tin can ameliorate production and employment. Thus the reduction of the trade deficit favours the country's growth.[75]

In January 1930, in the Economic Advisory Council, Keynes proposed the introduction of a system of protection to reduce imports. In the autumn of 1930, he proposed a uniform tariff of x% on all imports and subsidies of the same rate for all exports.[75] In the Treatise on Money, published in the autumn of 1930, he took up the thought of tariffs or other trade restrictions with the aim of reducing the volume of imports and rebalancing the balance of merchandise.[75]

On seven March 1931, in the New Statesman and Nation, he wrote an article entitled Proposal for a Tariff Revenue. He pointed out that the reduction of wages led to a reduction in national demand which constrained markets. Instead, he proposes the idea of an expansionary policy combined with a tariff system to neutralise the effects on the balance of trade. The application of customs tariffs seemed to him "unavoidable, whoever the Chancellor of the Exchequer might be".Thus, for Keynes, an economic recovery policy is just fully effective if the trade deficit is eliminated. He proposed a 15% tax on manufactured and semi-manufactured goods and 5% on sure foodstuffs and raw materials, with others needed for exports exempted (wool, cotton fiber).[75]

In 1932, in an article entitled The Pro- and Anti-Tariffs, published in The Listener, he envisaged the protection of farmers and certain sectors such as the automobile and iron and steel industries, because them indispensable to United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland.[75]

The critique of the theory of comparative advantage [edit]

In the post-crisis situation of 1929, Keynes judged the assumptions of the gratis trade model unrealistic. He criticised, for case, the neoclassical assumption of wage adjustment.[75] [76]

Every bit early on every bit 1930, in a note to the Economic Informational Council, he doubted the intensity of the proceeds from specialisation in the example of manufactured goods. While participating in the MacMillan Committee, he admitted that he no longer "believed in a very high degree of national specialisation" and refused to "abandon whatever industry which is unable, for the moment, to survive". He also criticised the static dimension of the theory of comparative advantage, which, in his view, by fixing comparative advantages definitively, led in practice to a waste of national resources.[75] [76]

In the Daily Mail of 13 March 1931, he chosen the assumption of perfect sectoral labour mobility "nonsense" since it states that a person made unemployed contributes to a reduction in the wage rate until he finds a job. Only for Keynes, this change of task may involve costs (job search, training) and is not ever possible. Generally speaking, for Keynes, the assumptions of full employment and automatic return to equilibrium discredit the theory of comparative advantage.[75] [76]

In July 1933, he published an article in the New Statesman and Nation entitled National Self-Sufficiency, in which he criticised the argument of the specialisation of economies, which is the basis of gratuitous trade. He thus proposed the search for a certain degree of self-sufficiency. Instead of the specialisation of economies advocated by the Ricardian theory of comparative reward, he prefers the maintenance of a diversity of activities for nations.[76] In it he refutes the principle of peacemaking trade. His vision of merchandise became that of a system where strange capitalists compete for new markets. He defends the idea of producing on national soil when possible and reasonable and expresses sympathy for the advocates of protectionism.[77] He notes in National Self-Sufficiency:[77] [75]

A considerable degree of international specialization is necessary in a rational world in all cases where information technology is dictated by broad differences of climate, natural resources, native aptitudes, level of culture and density of population. Only over an increasingly broad range of industrial products, and peradventure of agricultural products also, I have get doubtful whether the economical loss of national self-sufficiency is dandy enough to outweigh the other advantages of gradually bringing the production and the consumer within the catenary of the same national, economic, and financial organization. Experience accumulates to prove that most modern processes of mass production can be performed in most countries and climates with almost equal efficiency.

He also writes in National Self-Sufficiency:[75]

I sympathize, therefore, with those who would minimize, rather than with those who would maximize, economic entanglement amidst nations. Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel--these are the things which should of their nature exist international. Simply permit goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, to a higher place all, allow finance be primarily national.

Afterwards, Keynes had a written correspondence with James Meade centred on the effect important restrictions. Keynes and Meade discussed the best choice between quota and tariff. In March 1944 Keynes began a word with Marcus Fleming after the latter had written an article entitled Quotas versus depreciation. On this occasion, we come across that he has definitely taken a protectionist opinion after the Dandy Depression. He considered that quotas could be more effective than currency depreciation in dealing with external imbalances. Thus, for Keynes, currency depreciation was no longer sufficient and protectionist measures became necessary to avoid merchandise deficits. To avoid the return of crises due to a cocky-regulating economical system, it seemed essential to him to regulate trade and stop free trade (deregulation of strange trade).[75]

He points out that countries that import more than they consign weaken their economies. When the merchandise deficit increases, unemployment rises and Gdp slows downwardly. And surplus countries exert a "negative externality" on their trading partners. They get richer at the expense of others and destroy the output of their trading partners. John Maynard Keynes believed that the products of surplus countries should exist taxed to avoid trade imbalances.[78] Thus he no longer believes in the theory of comparative reward (on which free merchandise is based) which states that the trade deficit does not thing, since trade is mutually beneficial. This also explains his want to supercede the liberalisation of international trade (Complimentary Trade) with a regulatory arrangement aimed at eliminating merchandise imbalances in his proposals for the Bretton Woods Agreement.

Arguments against tariffs [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. You lot can help by adding to it. (October 2021) |

Trade liberalization can sometimes result in big and unequally distributed losses and gains, and tin can, in the short run, crusade significant economic dislocation of workers in import-competing sectors.

Despite an intuitive understanding of many of the benefits of free trade, the general public has strong reservations about embracing such a policy. One set of reservations concerns distributional effects of trade. Workers are not seen equally benefiting from trade. Strong show exists indicating a perception that the benefits of trade flow to businesses and the wealthy, rather than to workers, and to those abroad rather than to those in the U.s..[eight]

—William Poole, Federal Reserve Banking concern of St. Louis Review, September/October 2004, page 2

.

See also [edit]

References [edit]

- ^ Krugman, Paul R. (May 1993). "The Narrow and Wide Arguments for Complimentary Trade". American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings. 83 (iii): 362–366. JSTOR 2117691.

- ^ Krugman, Paul R. (1994). Peddling Prosperity: Economic Sense and Nonsense in the Age of Diminished Expectations. New York: W.W. Norton & Visitor. ISBN9780393312928.

- ^ "Free Trade". IGM Forum. March 13, 2012.

- ^ "Import Duties". IGM Forum. October iv, 2016.

- ^ N. Gregory Mankiw, Economists Actually Agree on This: The Wisdom of Free Trade, New York Times (April 24, 2015): "Economists are famous for disagreeing with 1 another.... Just economists reach virtually unanimity on some topics, including international trade."

- ^ Poole, William (2004). "Gratuitous Merchandise: Why Are Economists and Noneconomists So Far Autonomously" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review. 86 (5): 1. doi:x.20955/r.86.1-6.

virtually observers agree that '[t]he consensus amongst mainstream economists on the desirability of free trade remains most universal.'

- ^ "Trade Within Europe | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org . Retrieved 2017-06-24 .

- ^ a b Poole, William (2004). "Free Trade: Why Are Economists and Noneconomists And so Far Autonomously" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review. 86 (v): 2. doi:ten.20955/r.86.1-vi.

1 fix of reservations concerns distributional effects of trade. Workers are not seen as benefiting from trade. Strong evidence exists indicating a perception that the benefits of trade catamenia to businesses and the wealthy, rather than to workers, and to those abroad rather than to those in the United States.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Everett (xi March 2016). "Here's why anybody is arguing about complimentary trade". CNBC. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ The Online Etymology Dictionary: tariff. The 2nd edition of the Oxford English Dictionary gives the aforementioned etymology, with a reference dating to 1591.

- ^ Steingass, Francis Joseph (1884). The student's Arabic-English dictionary. Cornell Academy Library. London : Due west.H. Allen. p. 178.

- ^ Lokotsch, Karl (1927). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der Europäischen (Germanischen, Romanischen und Slavischen) Wörter Orientalischen Ursprungs (in German). Universidad Francisco Marroquín Biblioteca Ludwig von Mises. Carl Winter'due south Universitätsbuchhandlung C. F. Wintersche Buchdruckerei. p. 160.

- ^ "Etimologia : tariffa;". www.etimo.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2021-09-10 .

- ^ "tariffa in Vocabolario - Treccani". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2021-09-x .

- ^ Kluge, Friedrich (1989). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (in German). Max Bürgisser, Bernd Gregor, Elmar Seebold (22. Aufl. ed.). Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 721. ISBN3-11-006800-1. OCLC 20959587.

- ^ Burke, Susan; Bairoch, Paul (June 1989). "Affiliate I - European trade policy, 1815–1914". In Mathias, Peter; Pollard, Sidney (eds.). The Industrial Economies: The Development of Economic and Social Policies. The Cambridge Economic History of Europe from the Turn down of the Roman Empire. Vol. 8. New York: Cambridge University Printing. pp. 1–160. doi:10.1017/chol9780521225045.002. ISBN978-0521225045.

- ^ Wilson, Nigel (2013-10-31). Encyclopedia of Ancient Hellenic republic. Routledge. ISBN978-1-136-78799-7.

- ^ Michell, H. (2014-08-14). The Economics of Ancient Hellenic republic. Cambridge Academy Press. p. 253. ISBN978-1-107-41911-7.

- ^ a b c d e f k h Ha-Joon Chang (Faculty of Economics and Politics, University of Cambridge) (2001). Infant Industry Promotion in Historical Perspective – A Rope to Hang Oneself or a Ladder to Climb With? (PDF). Evolution Theory at the Threshold of the Twenty-get-go Century. Santiago, Chile: United Nations Economical Committee for Latin America and the Caribbean. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2021-05-xiii .

- ^ Hugh Montgomery; Philip George Cambray (1906). A Lexicon of Political Phrases and Allusions : With a brusque bibliography. S. Sonnenschein. p. 33.

- ^ John C. Miller, The Federalist Era: 1789-1801 (1960), pp 14-15,

- ^ Percy Ashley, "Modern Tariff History: Deutschland, United States, France (tertiary ed. 1920) pp 133-265.

- ^ Robert V. Remini, "Martin Van Buren and the Tariff of Abominations." American Historical Review 63.4 (1958): 903-917.

- ^ a b c Chang, Ha-Joon; Gershman, John (2003-12-30). "Kicking Away the Ladder: The "Real" History of Gratuitous Trade". ips-dc.org. Constitute for Policy Studies. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Infant Manufacture Promotion in Historical Perspective– A Rope to Hang Oneself or a Ladder to Climb With? (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on eight March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Dorfman & Tugwell (1960). Early American Policy.

- ^ a b c d e Ha-Joon Chang. Kicking Away the Ladder: Evolution Strategy in Historical Perspective.

- ^ Bairoch (1993). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes . University of Chicago Press. ISBN9780226034621.

- ^ Thomas C. Cochran, William Miller (1942). The Age of Enterprise: A Social History of Industrial America.

- ^ R. Luthin (1944). Abraham Lincoln and the Tariff.

- ^ William K. Bolt, Tariff Wars and the Politics of Jacksonian America (2017) covers 1816 to 1861.

- ^ F.Westward. Taussig,. The Tariff History of the United states. 8th edition (1931); 5th edition 1910 is online

- ^ Robert Due west. Merry, President McKinley: Builder of the American Century (2017) pp 70-83.

- ^ "Republican Political party Platform of 1896 | the American Presidency Project".

- ^ a b "A historian on the myths of American trade". The Economist . Retrieved 2017-11-26 .

- ^ Irwin, Douglas A. (2011). Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression. p. 116. ISBN9781400888429.

- ^ Temin, P. (1989). Lessons from the Great Depression. MIT Printing. ISBN9780262261197.

- ^ "Russia Leads the Earth in Protectionist Merchandise Measures, Study Says". The Moscow Times. 10 January 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Russian federation was nearly protectionist nation in 2013: study". Reuters. 30 Dec 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Dwelling house - Make In Bharat". www.makeinindia.com . Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Import duty hike on consumer durables, 'Make in India' drive to get a boost". www.indiainfoline.com . Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "India doubles import tax on material products, may hit Red china". Reuters. 7 August 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2019 – via world wide web.reuters.com.

- ^ "Republic of india to raise import tariffs on electronic and communication items". Reuters. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 14 Apr 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "Armenia - Import Tariffs". export.gov. 2015-01-02. Retrieved 2019-ten-07 .

- ^ "Specific Annex D: Community Warehouses and Free Zones", International Convention on the Simplication and Harmonization of Customs Procedures (Revised Kyoto Convention), Globe Community System, 1999

- ^ a b c Krugman, Paul and, Wells, Robin (2005). Microeconomics. Worth. ISBN978-0-7167-5229-five.

- ^ a b Radcliffe, Brent. "The Basics Of Tariffs and Merchandise Barriers". Investopedia . Retrieved 2020-11-07 .

- ^ "Steel and Aluminum Tariffs". www.igmchicago.org. March 12, 2018. Retrieved 2019-10-07 .

- ^ Krugman & Wells (2005).

- ^ Diamond, Peter A.; Mirrlees, James A. (1971). "Optimal Revenue enhancement and Public Production I: Product Efficiency". The American Economical Review. 61 (1): 8–27. JSTOR 1910538.

- ^ Furceri, Davide; Hannan, Swarnali A; Ostry, Jonathan D; Rose, Andrew G (2021). "The Macroeconomy After Tariffs". The World Banking company Economic Review. 36 (2): 361–381. doi:10.1093/wber/lhab016. ISSN 0258-6770.

- ^ El-Agraa (1984), p. 26.

- ^ Almost all real-life examples may be in this case.

- ^ El-Agraa (1984), pp. eight–35 (in 8–45 by the Japanese ed.), Chap.ii 保護:全般的な背景.

- ^ El-Agraa (1984), p. 76 (by the Japanese ed.), Chap. five 「雇用-関税」命題の政治経済学的評価.

- ^ El-Agraa (1984), p. 93 (in 83-94 past the Japanese ed.), Chap. 6 最適関税、報復および国際協力.

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson – under George Washington by America'due south History". americashistory.org. Archived from the original on 2012-07-08.

- ^ "Behind the Steel-Tariff Curtain". Business Week Online. March viii, 2002.

- ^ Sid Marris and Dennis Shanahan (November 9, 2007). "PM rulses out more assist for car firms". The Australian. Archived from the original on 2007-xi-09. Retrieved 2007-11-11 .

- ^ "Candidate wants car tariff cuts halted". The Age. Melbourne. Oct 29, 2007.

- ^ (in Spanish) Primeros movimientos sociales chileno (1890–1920). Memoria Chilena.

- ^ Benjamin S. 1997. Meat and Forcefulness: The Moral Economic system of a Chilean Food Riot. Cultural Anthropology, 12, pp. 234–268.

- ^ "International trade - Arguments for and against interference". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Graham Dunkley (4 April 2013). Free Trade: Myth, Reality and Alternatives. ISBN9781848136755.

- ^ "Challenges of African Growth" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September xv, 2012. Retrieved 2019-10-07 .

- ^ Chang, Ha-Joon (xv July 2012). "Africa needs an agile industrial policy to sustain its growth - Ha-Joon Chang". Retrieved 14 April 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ a b "Why does Africa struggle to industrialise its economies? | The New Times | Rwanda". The New Times. 2016-08-thirteen. Retrieved 2019-ten-07 .

- ^ "Macroeconomic effects of Chinese mercantilism". The New York Times. 31 December 2009.

- ^ Martina, Michael (16 March 2017). "U.S. tech group urges global action against Chinese "mercantilism"". Reuters – via world wide web.reuters.com.

- ^ Pham, Peter. "Why Do All Roads Lead To Cathay?". Forbes.

- ^ "Learning from Chinese Mercantilism". PIIE. 2 March 2016.

- ^ Professor Dani Rodik (June 2002). "After Neoliberalism, What?" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Ackerman, Frank (2005). "The Shrinking Gains from Merchandise: A Critical Cess of Doha Round Projections". Working Newspaper No. 05-01. doi:10.22004/AG.ECON.15580. S2CID 17272950.

- ^ Drusilla Thou. Chocolate-brown, Alan V. Deardorff and Robert M. Stern (December 8, 2002). "Computational Analysis of Multilateral Trade Liberalization in the Uruguay Round and Doha Development Round" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Maurin, Max (2011). "J.M. Keynes, le libre-échange et le protectionnisme". 50'Actualité Économique. 86: 109–129. doi:10.7202/045556ar.

- ^ a b c d Maurin, Max (2013). Les fondements non neoclassiques du protectionnisme (Thesis). Université Bordeaux-4.

- ^ a b "John Maynard Keynes, "National Self-Sufficiency," the Yale Review, Vol. 22, no. 4 (June 1933), pp. 755-769".

- ^ Joseph Stiglitz (2010-05-05). "Reform the euro or bin it". TheGuardian.com.

Sources [edit]

- El-Agraa, Ali One thousand. (1984). Trade THEORY AND POLICY . The Macmillan Press Ltd. ISBN9780333360200.

- Krugman, Paul; Wells, Robin (2005). Macroeconomics. Worth. ISBN978-0-7167-5229-five.

External links [edit]

![]() Media related to tariffs at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to tariffs at Wikimedia Commons

- Types of Tariffs

- Effectively applied tariff by Country 2008 to 2012

- MFN Trade Weighted Boilerplate Tariff by country 2008–2012

- World Bank'due south site for Trade and Tariff

- Market Admission Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements

- WTO Tariff Analysis Online – Detailed information on tariff and merchandise data

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tariff

Posted by: andersonhaplen57.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Who Pays Tariffs And Where Does That Money Go To"

Post a Comment